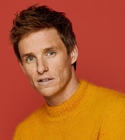

A tentative smile spreads across Eddie Redmayne’s face. “Anxiety is something that drives me,” he says quietly. “It has for a long time. Ultimately, I think, you only live once. If it’s a catastrophe, I got to play a part that always felt unfinished in me. If I don’t do it, then perhaps I will just live with regret.”

We are sitting in the gilded splendor of Fischer’s, a restaurant specializing in Austrian food in the Marylebone area of London, discussing Redmayne’s bold decision to return to the stage as the charismatic and mysterious Emcee in Cabaret. (Redmayne was last seen onstage 10 years ago, as Shakespeare’s Richard II; before that he starred in Red, as the fictional assistant of Mark Rothko, winning a Tony.) He’s chosen the restaurant because he likes the area—only when we order schnitzel and cucumber salad does he realize what an appropriate setting it is to talk about Berlin in 1929.

When Cabaret opens in London in November, it will be the second time Redmayne has played this part. He first gave it a go at 19, in a student production at the Edinburgh Fringe festival just after he left Eton. It was staged in a grotty, run-down venue called Underbelly. “I didn’t really see daylight, and became quite skeletal, and I remember finding it thrilling.” Fast-forward 20 years and that excitement is still there. So is Underbelly, which, under the guidance of its founders, Ed Bartlam and Charlie Wood, has morphed into an influential producing company that hosts festivals in London and Edinburgh and has produced hit shows. It was Bartlam who approached Redmayne to play the part again; Redmayne then asked Jessie Buckley, star of Wild Rose and Judy, whether she’d like to take on Sally Bowles, the singer whose story gives Cabaret its heart. “Jessie has this extraordinary spirit and an anarchic quality,” he says.

“It was a kind of no-brainer,” explains Buckley over Zoom from Toronto, where she has been filming Sarah Polley’s Women Talking. “I feel it’s like a blank canvas, a chance to go back to the theater and fall in love, which I haven’t done since my first job”—when she was cast in Trevor Nunn’s production of Sondheim’s A Little Night Music. Playing Sally, Buckley will be able to draw on her own experience as a young singer, fresh from Kerry in Ireland, when she worked in London’s Annabel’s nightclub. “It was so far away from where I grew up,” she says, “a world of secrets.” Buckley is an enthusiast, full of energy and commitment. “For Eddie it’s a passion project, and I was delighted he thought of me,” she says, smiling broadly.

Buckley and Redmayne were both fans of director Rebecca Frecknall, and he’d seen the final night of her groundbreaking production of Tennessee Williams’s Summer and Smoke in the West End in 2019. They approached her for Cabaret. Frecknall subsequently introduced Redmayne to designer Tom Scutt, who, together with ATG Productions and Underbelly, made the decision to convert The Playhouse, just off Trafalgar Square, into the fictional Kit Kat Club. “I’d seen Cabaret done formidably. I’d seen the film, and Sam Mendes’s production,” Redmayne says. “The only point in us doing it would be if we could do something different from those other productions, something new.”

When it premiered on Broadway, in 1966, Cabaret invented the concept musical. Based on Christopher Isherwood’s semi-autobiographical Goodbye to Berlin, it dealt with themes such as antisemitism and abortion, and in ways that were radical. Director Hal Prince had the Emcee play directly to the audience, outside the main thrust of the narrative: Sally’s relationship with the American writer Cliff (who will be played here by Omari Douglas). Prince’s notion was to make the cabaret a metaphor for Germany as the Nazis rose to power, putting the characters in a chilling historical context. Bob Fosse’s 1972 movie with Liza Minnelli added another iconic element to the mix.

For Frecknall, the challenge is to make sure its revolutionary quality comes through. “I am always interested in how you can tell this fresh,” she says. “There are a lot of things bubbling up: politics, gender, hierarchies, stereotyping, the human fear of otherness and difference and how that can be weaponized. Eddie brings an angle to it that’s unexpected.”

Redmayne’s casting has, in fact, caused disquiet in some quarters, Scutt explains. “The history of that role is one of queer portrayal.” This began with Joel Grey’s white-faced

take; it has been emphasized by other interpretations, including Alan Cumming’s mesmeric and menacing incarnation. (Grey and Cumming are both gay, while Redmayne is not.) Redmayne pauses for a moment when I bring this up. “I hope when people see the performance, the interpretation will justify the casting,” he says. “The way I see the character is as shape-shifting and a survivor.”

“Shape-shifting is a word we have been using a lot,” says Scutt. “And not just about Eddie. It feels like a metaphor for the period—a party at the end of the world.” In this, Buckley sees some parallels with the present: “They must have known that life was short,” she says. “What we are coming out of now is not a world war, but the fear of death is present.”

Despite the strictures of COVID, both Buckley and Redmayne have had busy years. Buckley spent some time at her new home in rural Norfolk before filming Alex Garland’s Men and then Women Talking. (She also appears in Maggie Gyllenhaal’s The Lost Daughter this fall.) In Redmayne’s case, COVID closed the set of J.K. Rowling’s Fantastic Beasts just as he was about to film the third installment. He spent lockdown in Staffordshire with his wife, Hannah, and his children, Iris, who is five, and Luke, three. “My wife is gently converting me to someone who knows his way around a veg patch,” he says, with obvious affection for the woman he married in 2014. “I loved it.

Iris was just learning to read, and Luke was just learning to talk. I felt very lucky to be around.”

Redmayne is clearly nervous about his return to the stage, yet his excitement keeps breaking through: “In theater, I had such luck with new plays, such fun, and I have not always had that on film. I have done some catastrophically bad films and had some great experiences. In theater, I’ve always found a wonderful alchemy.” Finding those moments of truth, when a chink of utter honesty is revealed, is Redmayne’s goal. “It’s the reason I love what I do, that rare moment when something becomes real. That’s the drug.” He smiles again, perhaps imagining the moment his Emcee steps out onstage, peels back the layers of artifice, and reveals something true. [Source]